notes on art: "each homer of nought"

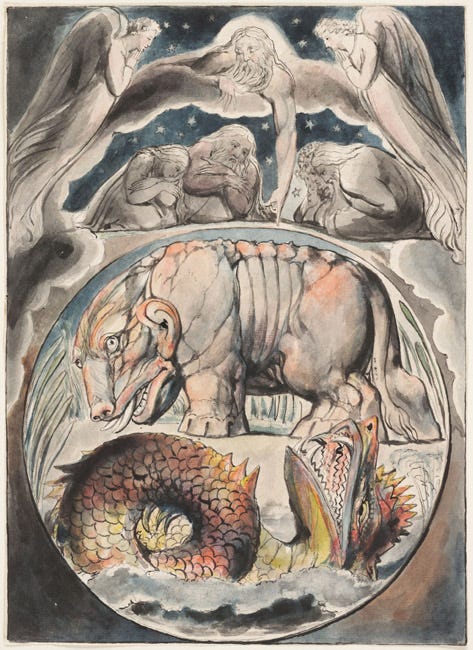

At the end of the pandemic which wasn't the end, the words hovered above the vellum, lambent and clear. And the deep said of wisdom: it is not here. Job seemed to me a joke whose punchline was "God." In this, it was also like life. It was my dead mother's bible that I was reading, and what I read was so strange that despite having read the bible through several times, I did not believe that what I was reading was the same book. The book I read now had something to do with mining, with heavy rocks and an earth dusted with gold. I checked the cover, which said "Bible," and the heading, which continued to say "Job."

Job, I thought, was a book of anti-epiphany, an undoing of the theory that everyone leaves events wiser. In order to teach writing I should take my students to the top of a mountain and then roll a boulder down it. That, I would point downhill, is the course of every plot, whether the writer knows it or not. Job didn't leave wiser, he left smaller and quieter.

Job is also about who has a GPS for the cosmos, and how it isn't us. We as a species almost never know where it's at, or even what it is. Science is another sedimentary myth on top of the other layers of sediment, which didn't mean that as a set of disciplines it lacked useful knowledge, only that whatever wisdom it suggested was marginal and drifting. Science is real, proclaimed a multitude of yard signs, ignoring that science is also fake. I have not seen a yard sign against reification.

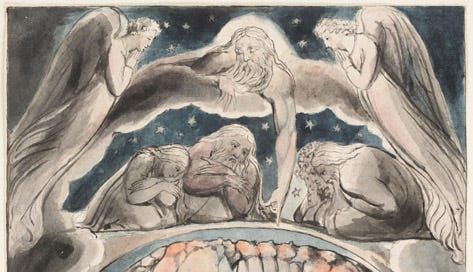

Of my complaints about the present, one is its limited palette of miracles. Or more likely, the miracles are many and often and everywhere but as we are trained in seeing patterns, we lack adequate perception to catch the one-off, except perhaps in the periphery of our vision, after a long day and too tired to discipline ourselves. If angels show up at all, it is fleetingly and in the corners of our eyes.

I have a different discipline: I draw angels with my eyes closed. De Kooning drew with his eyes closed. Allan Kaprow called what Jackson Pollock did "ecstatic blindness." But blindness is the wrong word, as this seeing does not entirely belong to normative sight. The inner eye so often has an unmatched power of synthesis, motion, generated light -- it composes, in part, by analogy, so it is able to see cumulatively and generatively from what we have only experienced in the sideways. Helen Keller wrote about this, "I understand how scarlet can differ from crimson because I know that the smell of an orange is not the smell of a grape-fruit," and "My hand has its share in this multiple knowledge, but it must never be forgotten that with the fingers I see only a very small portion of a surface... my imagination is not tethered to certain points, locations, and distances. It puts all the parts together simultaneously as if it saw or knew instead of feeling them."

I do not think the inner vision is any less material than the outer, but it might be deceptively cohesive, which can make the outer world, by comparison, appear bereft and fractured. This might be why, so often, the world looks wrong. I've had a difficult time believing I could share my writing, interested in wanting nothing and in the walled complexities of gardens and libraries, feeling exhausted, semi-sick, and lost. I did not know how the lost could write, or what we could say, or if we should say anything, until walking down the stairs from the attic, I had a revelation: how the lost can write is for the lost. And so we who draw angels with our eyes closed should not be bereft of our own literature, even as making it is a fragile activity, having only an embarrassed relation to capitalism's dire opinionating from platforms of carbon-economies and blood. The boulder rolled down hill is also it: all epic negationists, each Homer of nought, to write into an anti-history gold dust and undoing, litanies and laments, cantos of unwilling and unwant.